Art Work on Jesus and His Disciples at the Communion Table

The Terminal Supper of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles has been a pop subject in Christian fine art,[1] oft as part of a cycle showing the Life of Christ. Depictions of the Last Supper in Christian art date back to early Christianity and can exist seen in the Catacombs of Rome.[2] [3]

The Last Supper was depicted both in the Eastern and Western Churches.[2] By the Renaissance, information technology was a favorite subject in Italian art.[ii] Information technology was as well i of the few subjects to be continued in Lutheran altarpieces for a few decades subsequently the Protestant Reformation.[4]

In that location are 2 major scenes shown in depictions of the Last Supper: the dramatic annunciation of the betrayal of Jesus, and the institution of the Eucharist. Later the meal the further scenes of Jesus washing the feet of his apostles and the good day of Jesus to his disciples are likewise sometimes depicted.[1] [five]

Setting [edit]

The earliest known written reference to the Terminal Supper is in Paul's Outset Epistle to the Corinthians (11:23–26), which dates to the middle of the first century, between AD 54–55.[six] [7] The Last Supper was likely a retelling of the events of the last repast of Jesus among the early Christian community, and became a ritual which referred to that repast.[viii] The earliest depictions of such meals occur in the frescoes of the Crypt of Rome, where figures are depicted reclining around semi-circular tables.[2] In spite of near unanimous assent, the historicity of the testify, one alone scholar comments that "The motif of the Final supper appears neither among the paintings of the catacombs nor the sculptures on sarcophagi ... The few frescos in the catacombs representing a meal in which Christ and some of the disciples participate prove not the Last supper but refer to the futurity meal promised by the exalted Christ in his heavenly kingdom", seeing the subject as beginning to exist depicted in the 6th century.[9]

A clearer instance is the mosaic in the Church building of Sant' Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italia, where a like meal scene is role of a cycle depicting the life of Jesus and involves clear representation of him and his disciples. Byzantine artists sometimes used semi-circular tables in their depictions, but more frequently they focused on the Communion of the Apostles, rather than the reclining figures having a repast.[2] The Last Supper was too ane of the few subjects to be continued in Lutheran altarpieces for a few decades subsequently the Protestant Reformation, sometimes showing portraits of leading Protestant theologians every bit the apostles.[4]

Past the Renaissance, the Concluding Supper was a favorite subject in Italian art, especially in the refectories of monasteries. These depictions typically portrayed the reactions of the disciples to the announcement of the betrayal of Jesus.[ii] Most of the Italian depictions use an oblong table, and not a semi-circular one, and sometimes Judas is shown by himself clutching his coin purse.[2]

Last Supper by James Tissot, between 1886 and 1894. Tissot shows the Apostles as they well-nigh probably were eating the meal, on couches, as it was the custom of the time.

With an ellipsoidal tabular array, the artist had to decide whether to show the apostles on both sides, then with some seen from behind, or all on 1 side of the table facing the viewer. Sometimes only Judas is on the side nearest the viewer, allowing the bag to be seen. The placement on both sides was further complicated when halos were obligatory; was the halo to be placed as though in front end of the rear-facing apostles faces, or as though fixed to the back of their head, obscuring the view? Duccio, daringly for the fourth dimension, just omits the halos of the apostles nearest the viewer. As artists became increasingly interested in realism and the delineation of space, a three-sided interior setting became more clearly shown and elaborate, sometimes with a mural view behind, as in the wall-paintings by Leonardo da Vinci and Perugino.[ten] Artists who showed the scene on a ceiling or in a relief sculpture had further difficulties in devising a composition.

Typically, the simply apostles easily identifiable are Judas, ofttimes with his bag containing 30 pieces of silvery visible, John the Evangelist, normally placed on Jesus's right side, commonly "reclining in Jesus' bust" equally his Gospel says (run across below), or even comatose, and Saint Peter on Jesus's left. The food on the table often includes a paschal lamb; in Late Antiquarian and Byzantine versions fish was the principal dish. In afterwards works the bread may go more like a communion host, and more food, eating, and figures of servers appear.[11]

Major scenes [edit]

There are two major episodes or moments depicted in Last Supper scenes, each with specific variants.[1] There are besides other, less oftentimes depicted scenes, such as the washing of the feet of the disciples.[12]

The Betrayal [edit]

The beginning episode, much the well-nigh common in Western Medieval art,[13] is the dramatic and dynamic moment of Jesus' announcement of his expose. In this the various reactions produced past the Apostles and the depictions of their emotions provide a rich subject for artistic exploration,[one] following the text of Chapter xiii of the Gospel of John (21–29, a "sop" is a piece of bread dipped in sauce or wine):

21 When Jesus had thus said, he was troubled in the spirit, and testified, and said, Verily, verily, I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me.

22 The disciples looked one on another, doubting of whom he spake.

23 In that location was at the tabular array reclining in Jesus' bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.

24 Simon Peter therefore beckoneth to him, and saith unto him, Tell [us] who it is of whom he speaketh.

25 He leaning back, every bit he was, on Jesus' breast saith unto him, Lord, who is it?

26 Jesus therefore answereth, He it is, for whom I shall dip the sop, and give it him. So when he had dipped the sop, he taketh and giveth it to Judas, [the son] of Simon Iscariot.

27 And afterward the sop, then entered Satan into him. Jesus therefore saith unto him, What thou doest, do chop-chop.

28 Now no man at the table knew for what intent he spake this unto him.

29 For some thought, because Judas had the bag, that Jesus said unto him, Buy what things nosotros take demand of for the feast; or, that he should give something to the poor.

xxx He then having received the sop went out straightway: and information technology was dark.

Especially in Eastern depictions, Judas may only be identifiable because he is stretching out his hand for the food, every bit the other apostles sit down with hands out of sight, or because he lacks a halo. In the Due west he often has red hair. Sometimes Judas takes the sop in his mouth directly from Jesus' hand, and when he is shown eating it a small devil may be shown next to or on information technology.[14] The betrayal scene may besides be combined with the other episodes of the meal, sometimes with a second figure of Christ washing Peter'due south feet.[15]

The Eucharist [edit]

The second scene shows the institution of the Eucharist, which may exist shown as either the moment of the consecration of the bread and wine, with all still seated, or their distribution in the showtime Holy Communion, technically known in art history as the Communion of the Apostles (though in depictions set at the table the distinction is often not fabricated), which is common in very early depictions and throughout Byzantine art, and in the West reappears from the 14th century onwards.[16] The depictions of both scenes are mostly solemn and mystical; in the latter Jesus may be standing and delivers the communion bread and wine to each campaigner, similar a priest giving the sacrament of Holy Communion. In early on and Eastern Orthodox depictions the apostles may queue up to receive it, equally though in a church, with Jesus continuing under or next to a ciborium, the small-scale open up construction over the altar, which was much more than mutual in Early Medieval churches. An case of this type is in mosaic in the apse of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev, under a very large continuing Virgin.[17]

- Depictions of The Eucharist

-

-

Washing of feet and bye [edit]

The washing of feet was an element of hospitality normally performed by servants or slaves, and a mark of not bad respect if performed by the host. It is recorded in John xiii:1–15, every bit preceding the meal, and subsequently became a feature of Holy Calendar week liturgy and year-circular monastic hospitality at various times and places, being regularly performed by the Byzantine emperors on Maundy Thursday for example, and at times beingness part of English Royal Maundy ceremonies performed by the monarch. For a while it formed function of the Baptism ceremony in some places.[18] It mostly appears in cycles of the Passion of Jesus, oft next to the Last Supper meal and given equal prominence, as in the 6th century St Augustine Gospels and 12th century Ingeborg Psalter, and as well may appear in cycles of the Life of Saint Peter. Where space is express just Jesus and Peter may be shown, and many scenes show the amazement of Peter, following John.[12] [19] A number of scenes appear on 4th century sarcophagi, in one case placed to represent with a scene of Pontius Pilate washing his hands. Some types show Jesus continuing as he is confronted past Peter; in others he is bending or kneeling to perform the washing. The bailiwick had various theological interpretations which affected the composition, only gradually became less mutual in the West by the Tardily Middle Ages, though there are at least ii big examples by Tintoretto, one originally paired with a Last Supper.[xx]

The last episode, far less commonly shown, is the farewell of Jesus to his disciples, in which Judas Iscariot is no longer present, having left the supper; information technology is mostly found in Italian trecento painting. The depictions here are mostly melancholy, as Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure.[1]

- Depictions of Washing of feet and good day

-

Primal examples [edit]

Pietro Perugino'due south delineation (c. 1490) in Florence shows Judas sitting separately, and is considered one of Perugino'south all-time pieces.[21] It is located in the convent that housed noble Florentine girls.[22] Upon its rediscovery was initially attributed to Raphael.

Leonardo da Vinci'southward depiction (belatedly 1490s) which is considered the first work of High Renaissance art due to its loftier level of harmony, uses the first theme.[23] Leonardo counterbalanced the varying emotions of the individual apostles when Jesus stated that one of them would betray him, and portrayed the various attributes of acrimony, surprise and daze.[23] It is probable that Leonardo da Vinci was already familiar with Ghirlandaio's Concluding Supper, as well equally that of Castagno, and painted his ain Concluding Supper in a more dramatic class to dissimilarity with the stillness of these works, and so that more emotion would be displayed.[24]

Tintoretto's depiction (1590–1592) at the Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, also depicts the annunciation of the betrayal, and includes secondary characters carrying or taking the dishes from the table.[25]

There are far more than numerous secondary figures in the huge painting now called The Banquet in the House of Levi by Veronese. This was delivered in 1573 as a Last Supper to the Dominicans of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice for their refectory, only Veronese was called earlier the Inquisition to explicate why it contained "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" as well equally extravagant costumes and settings, in what is indeed a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician feast.[26] Veronese was told that he must change his painting within a three-calendar month period - in fact he simply changed the championship to the present one, nonetheless an episode from the Gospels, merely a less doctrinally fundamental ane, and no more was said.[27]

The altarpiece of the main church building in Martin Luther's habitation of Wittenberg is by Lucas Cranach the Elder (with his son and workshop), with a traditional representation of the Last Supper in the main panel, except that the apostle having a drink poured is a portrait of Luther, and the server may be one of Cranach. Past the time the painting was installed in 1547, Luther was dead. Other panels prove the Protestant theologians Philipp Melanchthon and Johannes Bugenhagen, pastor of the church, though non in biblical scenes. Other figures in the panels are probably portraits of figures from the boondocks, at present unidentifiable.[28] Another work, the Altarpiece of the Reformers in Dessau, by Lucas Cranach the Younger (1565, see gallery) shows all the apostles except Judas every bit Protestant churchmen or nobility, and it is now the younger Cranach shown as the cupbearer. However such works are rare, and Protestant paintings soon reverted to more traditional depictions.[29]

In Rubens' Last Supper, a dog with a os tin be seen in the scene, probably a uncomplicated pet. It may correspond faith, dogs are traditionally symbols of and are representing faith.[30] According to J. Richard Judson the canis familiaris nigh Judas, it perhaps representing greed, or representing the evil, equally the companion of Judas, every bit in John 13:27.[31]

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, Salvador Dalí's delineation, combines the typical Christian themes with modern approaches of Surrealism and too includes geometric elements of symmetry and polygonal proportion.[32]

Gallery [edit]

- Depictions of The Last Supper in Christian art

-

-

Judas reaches for the food; School of Monte Cassino, c. 1100, Sant'Angelo in Formis, Capua, still using Roman couches.

-

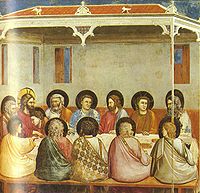

Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, 1305, with apartment perspectival haloes; the view from behind causes difficulties, and John's halo has to exist reduced in size.

-

Christ Washing the Feet of the Apostles by Meister des Hausbuches, 1475; only Judas (near correct) lacks a halo

-

Ottheinrich Page, p. 40v: Last Supper, Mt 26:xx–29

-

-

Meet also [edit]

- Ascension of Jesus in Christian art

- Christian fine art

- Art in Roman Catholicism

- The Reformation and art

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Gospel Figures in Art by Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0-89236-727-6 pp. 254–259 Google books link

- ^ a b c d e f g Vested Angels: Eucharistic Allusions in Early on Netherlandish Paintings by Maurice B. McNamee 1998 ISBN 978-90-429-0007-three pp. 22–32 Google books link

- ^ Christian Art, Volume 2007, Part 2 by Rowena Loverance ISBN 0-674-02479-six, 978-0-674-02479-3 p. Google books link

- ^ a b Schiller, forty–41

- ^ Schiller, 24–38

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, 2005 ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5 pp. 52–56 Google books link

- ^ "Introduction to the Epistles to the Corinthians - Study Resources".

- ^ The Church According to the New Testament by Daniel J. Harrington 2001 ISBN 1-58051-111-2 p. 49 Google books link

- ^ Schiller, 27–28

- ^ Schiller, 37

- ^ Schiller, 31, 37

- ^ a b Gospel Figures in Fine art past Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0-89236-727-6 p. 252 Google books link

- ^ Schiller, 32-38

- ^ Schiller, xxx–34, 37

- ^ Schiller, 32–33, 37–38

- ^ Schiller, 38–twoscore

- ^ Schiller, 28–xxx

- ^ Schiller, 41–42

- ^ Schiller, 42–43

- ^ Schiller, 42–47; National Gallery, London for the paired Tintoretto, an even larger one is in the Prado.

- ^ Florence: world cultural guide by Bruno Molajoli 1972 ISBN 978-0-03-091932-9 p. 254

- ^ Italian Art by Gloria Fossi, Marco Bussagli 2009 ISBN 880903726X p. 196 Google books link

- ^ a b Experiencing Art Effectually Us past Thomas Buser 2005 ISBN 978-0-534-64114-six pp. 382–383 Google books link

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper: a Cosmic Drama and an Act of Redemption by Michael Ladwein 2006 pp. 27, 60. Google books link

- ^ Tintoretto: Tradition and Identity by Tom Nichols 2004 ISBN 1-86189-120-ii p. 234 Google books link

- ^ "Transcript of Veronese's testimony". Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2011-04-18 .

- ^ David Rostand, Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, 2nd ed 1997, Cambridge Up ISBN 0-521-56568-5

- ^ Noble, 97–104; Schiller, 41

- ^ Schiller, 41

- ^ Viladesau, Richard (2014). The Desolation of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts – the Baroque Era. Oxford Academy Press. p. 26. ISBN9780199352692 . Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ Rubens: the passion of Christ by J. Richard Judson 2000 ISBN 0-905203-61-5 p. 49

- ^ The Mathematics of Harmony past Alexey Stakhov, Scott Olsen 2009 ISBN 978-981-277-582-5 pp. 177–178 Google books link

References [edit]

- Noble, Bonny, Lucas Cranach the Elder: Fine art and Devotion of the High german Reformation, Academy Press of America, 2009, ISBN 0-7618-4338-8, ISBN 978-0-7618-4338-two

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Fine art, Vol. II, 1972 (English trans from German language), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last_Supper_in_Christian_art

0 Response to "Art Work on Jesus and His Disciples at the Communion Table"

Mag-post ng isang Komento